|

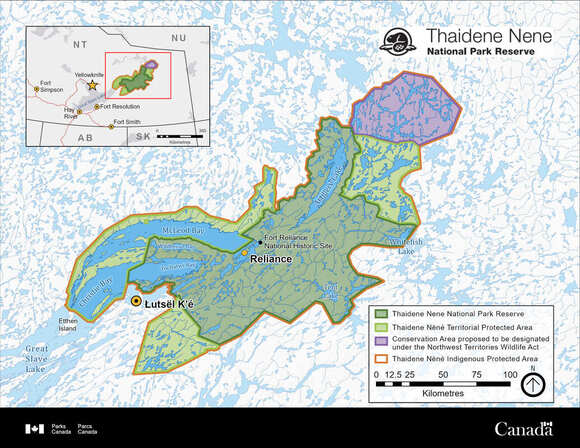

Portions of the Thaidene Nëné Indigenous Protected Area have been designated a national park reserve (NPR), a territorial protected area (TPA), and a wildlife conservation area (WCA) through agreements with Parks Canada and the GNWT. While visitors are expected to respect the land regardless of which part of the Thaidene Nëné Indigenous Protected Area they are in (see the Visitor Code of Conduct), there are some variations in expectations for the different parts of Thaidene Nëné Indigenous Protected Area.  For example, a valid Parks Canada fishing permit is required for recreational fishing in the waters of Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve (dark green on the map), which include Wildbread Bay, Charlton Bay and portions of Christie and McLeod Bays in Tu Nedhé (Great Slave Lake). A NWT fishing licence is required in Thaidene Nene Territorial Protected Area (light green on the map) and the Thaidene Nene Wilderness Conservation Area (purple on the map). Fishing permits and fishing licences are not required for traditional harvesting by Indigenous peoples for food, social, and ceremonial purposes. Parks Canada fishing permits are different from those issued by the Government of the Northwest Territories. Fishing permit fees are being waived until March 31, 2022. Even though permits are free this year, they are still required in the waters of the National Park Reserve. Parks Canada fishing permits are available online using the Parks Canada website or in-person for guests at Frontier Lodge or Trophy Fishing Lodge.

Our second Thaidene Nëné Newsletter is off to the printers! We will have paper copies for community members this weekend. In the meantime, check out the digital version. In this newsletter, we celebrate our Premier's Award, look back on December's Old Snowdrift On the Land Camp, and give updates about Ni Hat'ni Dene, Frontier Lodge, and local tourism activities. If you have suggestions for the newsletter or for Thaidene Nëné communications and/or operations, please let us know. Our door is always open. The March 2021 Thaidene Nëné Newsletter is available here. Under the guidance of Elder and Camp Coordinator JC Catholique, Thaidene Nëné Ni Hat’ni Dene Guardians and Ni Hadi Xa Traditional Knowledge Monitors will be providing youth from the Łutsël K’é Dene School with hands-on learning opportunities during a week-long culture camp and spring hunt planned for March 11-21. The camp is being co-sponsored by the Łutsël K’é Dene School, LKDFN Wellness Department, LKDFN Wildlife, Lands, and Environment Department, Parks Canada, and Nature United.

Camp activities will include: camp set up and take down, wood harvesting, ice harvesting, hunting, dry meat making, butchering, setting fish nets, checking fish nets, ice fishing, fixing fish, story telling, traditional land use areas, navigation, traditional and modern ice safety awareness, safe travel, trip planning, old cabin excursion, graveyard site, and as always the teaching of the fundamental Dene Laws. This is part of a series of profiles about the staff, leaders, and community members who are hard at work implementing Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation's vision for the Thaidene Nëné Indigenous Protected Area. You can read the other profiles here. When Darryl Marlowe was first elected chief of the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation in March 2017, he was 30 years old, making him the youngest person in the community’s history to hold that office. Darryl was happy to have been re-elected for a second term in October 2020: “I really enjoy working for my people, protecting our land, protecting our treaty rights, protecting our inherent rights.”

When he’s not advocating for his people and Thaidene Nëné, Darryl loves spending time on the land with his family, including his five children. Darryl was taught to travel and live on the land by his grandparents, George and Celine Marlowe and Henry King and Maryrose Boucher, and his parents, Kenneth and Elizabeth Boucher. He also found a skilled and willing mentor in his father-in-law, Archie Catholique, who’s been taking Darryl out hunting by boat and skidoo since he was 16. It is not just the skills needed to be a hunter that were passed on to Darryl, but also Dënesųłıné ethics: “When we go out, we go out as a group. We hunt together and stay together. We help each other, we take care of each other. We also respect the land and the animal. Every time we harvest an animal, we are grateful. We put down tobacco. We say thank you to the animal’s spirit. That animal giving its life allows us to provide for our families.” While Darryl loves to visit Ts’ąkuı Theda (Lady of the Falls) and Kaché (Fort Reliance), all of Thaidene Nëné is special for the chief, which is why he feels so strongly about the community’s decision to designate it an Indigenous protected area: “We are protecting the heart of our traditional territory from development for the long term. We want to ensure that our way of life, our culture, our land, our water, our animals will be protected for many years to come.” In protecting Thaidene Nëné, the community of Łutsël K’é is seeking to realize the vision of their ancestors through guidance provided by the elders. Darryl explains, “Everything that we have done is for the future. That’s what our elders used to say: yunedhé xa, which means for the future. All of this work is for future generations. We are leaving them a legacy.” Darryl wasn’t even born when the discussions of a park first surfaced, but he is honoured to have been able to be part of the process in recent years. In particular, he is proud of the way the community has worked with other partners to have portions of the Thaidene Nëné Indigenous Protected Area designated as a national park reserve, a territorial protected area, and a wildlife conservation area: “I’m glad we took the initiative to develop relationships with two crown governments. At a time when people are talking about reconciliation, we are an example for the rest of the country.” In addition to providing the heart of the community’s traditional territory with long-term protection from development, Darryl envisions other benefits for the community as they work to develop a tourism and conservation economy through Thaidene Nëné, including employment that is sustainable and meaningful for Łutsël K’é Dene. Darryl is particularly enthusiastic about the possibilities afforded by Ni Hat’ni Dene. As Darryl notes, “It’s a dream job for people because they get to spend time out on the land.” As importantly, the community relies on the guardians “to ensure that people are being respectful of Łutsël K’é’s traditional territory.” At present, all of the guardians are men. Going forward, Darryl would like to see women on the crew: “They can inspire and open up opportunities for younger generations.” With a national park reserve and territorial protected area within its borders, Thaidene Nëné will welcome visitors from across the territory, the country, and around the world. Darryl would like to remind visitors that Thaidene Nëné is sacred for the Łutsël K’é Dene, but also that the community depends on the land to sustain itself and its way of life: “Our elders modelled respect for the land. It is our responsibility as young leaders to do the same and to pass this teaching on to others.” This is part of a series of profiles about the staff, leaders, and community members who are hard at work implementing Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation's vision for the Thaidene Nëné Indigenous Protected Area. You can read the other profiles here. JC Catholique was born on the land at Thaılı, the mouth of the Snowdrift River. After a short stint at the local day school, JC went to residential school when he was seven years old. “I can’t really say that I grew up in the community,” he says, “because I was away for so long.” JC attended Peter Pond School in Fort Resolution, Breynat Hall in Fort Smith, and finally Akaitcho Hall in Yellowknife. After graduation, he worked as a production technician with a video crew at Yellowknife’s Tree of Peace Friendship Centre.

JC returned to Łutsël K’é in 1975. He had a number of different jobs in the years the following, including managing the Łutsël K’é Coop. His life changed dramatically when he stopped drinking in 1985. For the next two years, he worked as a drug and alcohol counsellor before deciding he wanted to go back to school in 1987. JC completed a certificate in Indian communications arts in 1990 and a bachelor’s degree in social work in 2004, both at the First Nations University in Regina, SK. In the interim, he returned to his job as a drug and alcohol counsellor in Łutsël K’é. After finishing his social work practicum in Fort Smith, JC was hired as a social worker by the local health authority there, a position he held for three years. In 2007, when JC was hired as a cultural coordinator by the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation, he moved back to his community. With the support of his Elders, JC worked to revitalize some of the community’s cultural traditions. His accomplishments include reviving drumming, fire ceremony, and handgames with the youth. JC’s work built on other revitalization projects, including the revival of the spiritual gathering at Desnedhe Che. Initiated by the Elders in 1989, the spiritual gathering has become an important annual event for the community. When a social work position opened up in Łutsël K’é in 2009, JC applied and was successful. He remained in this position until his retirement in 2020. JC’s uncle, Pierre Catholique, was Chief when the Government of Canada first proposed a national park on the East Arm of Tu Nedhé (Great Slave Lake) in 1970. JC was living in Yellowknife at the time, but he remembers hearing about the government’s proposal. “The idea of a national park upset a lot of people. We already had a national park,” he says, referring to Wood Buffalo National Park in Fort Smith. “There were a lot of bad stories coming from there. The people couldn’t hunt in the park, couldn’t take anything out of it, even though they were born there, living there.” The idea of a park resurfaced periodically, though it never had community support. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the people of Łutsël K’é seriously considered the idea. People became concerned, JC remembers, as they watched the diamond mines move into their territory. While there was a desire to protect their homeland, Łutsël K’é Dene remained skeptical about “the national park idea.” Ultimately, the Elders directed the Chief and Council and the community to find a way to protect their traditional land. It took years for the community to find a solution. “There were many public meetings,” JC recalls. “Leaders went from house to house, hearing concerns.” Eventually, through those discussions and meetings, “the community came to the idea that a national park could work but we had to use our own traditional laws, our Dene law,” to designate the area. The name Thaidene Nëné, which means “Land of Our Ancestors,” was chosen by the Elders. In the end, there was overwhelming support for the protected area. “More than 80% of our people voted in favour,” he says. JC participated in the meetings and discussions about Thaidene Nëné throughout this period as a community member. With his appointment to Thaidene Nëné Xá Dá Yáłtı, the management board for the Indigenous protected area, JC now has a formal role in providing strategic guidance to the parties as they implement Łutsël K’é’s vision for Thaidene Nëné. Thaidene Nëné is important, JC believes, because it protects the sacred area of the Dënesųłıné people: Ts’ąkwı Theda (Where the Old Lady Sits). “That area is special…sacred. Every time I go there, it brings me back in time. Everything is clean, quiet, all kinds of wildlife around. It is both a reminder and an example of how things should be not only for us, but for people all over the world.” For JC, Thaidene Nëné is about more than an opportunity to protect the land of his ancestors. It also presents an opportunity to revitalize Dënesųłıné governance, to move away from the institutions and practices imposed by colonial government, like the Indian Act. “The idea of using our own Dene Law was interesting. It made me think. What are our laws?” Answering that question is no small task. As JC notes, “There’s nothing written down. There’s no library for reference. Our guidance are the Elders and what we believe to be true from our heart.” Dene governance, JC has come to understand, is about people coming together and discussing the issue at hand. “When any kind of situation happens, we come together. We talk about it and come to an agreement. Everyone has a say and we all agree to the final outcome. It’s consensus style of governance.” It’s this fundamental principal of Dene governance, consensus, that is the foundation of Thaidene Nëné Xá Dá Yáłtı. JC thanks the Elders for their vision. “They set up that management board with GNWT and Parks Canada,” he says. “It’s good when everyone has the same vision, the same goal.” For all that Thaidene Nëné means to the people of Łutsël K’é, JC also thinks it can be a life-changing experience for visitors: “It will have a big impact on them and will maybe even change their perspective on how they view the land and nature. I think people can get energized just by being out here. They can also have a different outlook of things, of the environment.” In particular, “they can see what the environment is like when it’s clean.” Such an experience may inspire them to care for the land in the places they call home but also to care for themselves. “A person who is in tune with nature,” JC believes, “is also in tune with themselves.” Looking to the future, JC imagines “something like Banff National Park” for Thaidene Nëné with Łutsël K’é as the hub. “It would be good to welcome visitors year-round,” he says. “We have four distinct seasons—fall, winter, spring, summer. People can do different things in each season.” This will require more infrastructure. JC envisions an expanded airport, hotels and cabins at Duhamel Lake, and more opportunities for the community to showcase Dënesųłıné ways of life. The community will change, JC notes, but it will be worth it to choose tourism over industrial development, not only for the sake of the land but also for the people. “People experience life in different ways. For us Dene people, we experience life close to the land. We love our land. It provides a way of life for us. We live in an environment where there are many opportunities, but we have to work for it.” The Thaidene Nëné Indigenous Protected Area ensures that the intimate relationship that the Łutsël K’é Dene have with the land will continue long into the future. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

CONNECT |

VISIONWe are the Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation. Our vision for Thaidene Nëné is:

Nuwe néné, nuwe ch'anıé yunedhé xa (Our land, our culture for the future). We’re working with our partners to permanently protect Thaidene Nëné—part of our huge and bountiful homeland around and beyond the East Arm of Tu Nedhé. |